Principal quantum number

In atomic physics, the principal quantum symbolized as n is the first of a set of quantum numbers (which includes: the principal quantum number, the azimuthal quantum number, the magnetic quantum number, and the spin quantum number) of an atomic orbital. The principal quantum number can only have positive integer values. As n increases, the orbital becomes larger and the electron spends more time farther from the nucleus. As n increases, the electron is also at a higher potential energy and is therefore less tightly bound to the nucleus. This is the only quantum number introduced by the Bohr model.

For an analogy, one could imagine a multistoried building with an elevator structure. The building has an integral number of floors, and a (well-functioning) elevator can only stop at a particular floor. Furthermore the elevator can only travel an integer number of levels. As with the principal quantum number, higher numbers are associated with higher potential energy.

Of course beyond this point the analogy breaks down. In the case of elevators the potential energy is gravitational but with the quantum number it is electromagnetic. The gains and losses in energy are approximate with the elevator, but precise with quantum state. The elevator ride from floor to floor is continuous whereas quantum transitions are discontinuous. Finally the constraints of elevator design are imposed by the requirements of architecture, but quantum behavior reflects fundamental laws of physics.

Derivation

There are a set of quantum numbers associated with the energy states of the atom. The four quantum numbers n, ℓ, m, and s specify the complete and unique quantum state of a single electron in an atom called its wavefunction or orbital. Two electrons belonging to the same atom can not have the same four quantum numbers, due to the Pauli exclusion principle. The wavefunction of the Schrödinger wave equation reduces to the three equations that when solved lead to the first three quantum numbers. Therefore, the equations for the first three quantum numbers are all interrelated. The principal quantum number arose in the solution of the radial part of the wave equation as shown below.

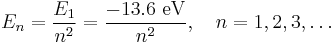

The Schrödinger wave equation describes energy eigenstates having corresponding real numbers En with a definite total energy which the value of En defines. The bound state energies of the electron in the hydrogen atom are given by:

The parameter n can take only positive integer values. The concept of energy levels and notation was utilized from the earlier Bohr model of the atom. Schrödinger's equation developed the idea from a flat two-dimensional Bohr atom to the three-dimensional wave function model.

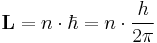

In the Bohr model, the allowed orbits were derived from quantized (discrete) values of orbital angular momentum, L according to the equation

where n = 1, 2, 3, … and is called the principal quantum number, and h is Planck's constant. This formula is not correct in quantum mechanics as the angular momentum magnitude is described by the azimuthal quantum number, but the energy levels are accurate and classically they correspond to the sum of potential and kinetic energy of the electron.

The principal quantum number n represents the relative overall energy of each orbital, and the energy of each orbital increases as the distance from the nucleus increases. The sets of orbitals with the same n value are often referred to as electron shells or energy levels.

The minimum energy exchanged during any wave-matter interaction is the wave frequency multiplied by Planck's constant. This causes the wave to display particle-like packets of energy called quanta. The difference between energy levels that have different n determine the Emission spectrum of the element.

In the notation of the periodic table, the main shells of electrons are labeled:

- K (n = 1), L (n = 2), M (n = 3), etc.

based on the principal quantum number.

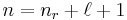

The principal quantum number is related to the radial quantum number, nr, by:

where ℓ is the azimuthal quantum number and nr is equal to the number of nodes in the radial wavefunction.